Diagnosis of Mastitis in Cows

Early identification of all cases of clinical mastitis is a key weapon in preventing further outbreaks of mastitis and is a key part of the overall mastitis control programme, ensuring maximum herd health, milk quality and dairy farm profitability.

The organisms that cause mastitis in dairy cows are divided into 2 main groups; contagious and environmental mastitis. There is some degree of interplay between these two types, for example strep uberis is primarily an environmental organism that can become ‘cow adapted’ and change into a contagious organism.

Each type of mastitis may present in an entirely different way. For example as infection with Staphylococcus aureus progresses through a herd the incidence of clinical mastitis may be quite low but the herd cell count continues to rise.

Streptococcus uberis may present with a high level of clinical cases and fluctuating bactoscans and herd somatic cell counts. Once ‘cow adapted’ strains of Strep uberis develop the herd cell count will increase rapidly due to the contagious transfer of infection.

Each farm has its own mastitis profile and the first task when investigating a problem is to establish the main organisms involved.

This can be assessed in two ways:

Take a bulk milk sample under strict conditions and submit it for specialist examination.

Take samples from each case of mastitis and store them in the freezer. These can then be analysed at a later date for the causative organisms.

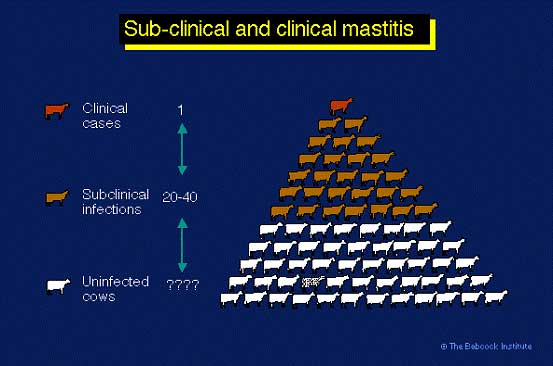

Subclinical Mastitis

The most important economic loss from mastitis is subclinical mastitis, for every clinical case of mastitis in a dairy herd there can be 25 or more subclinical cases. These subclinical cases are the main cause of increased cell counts:

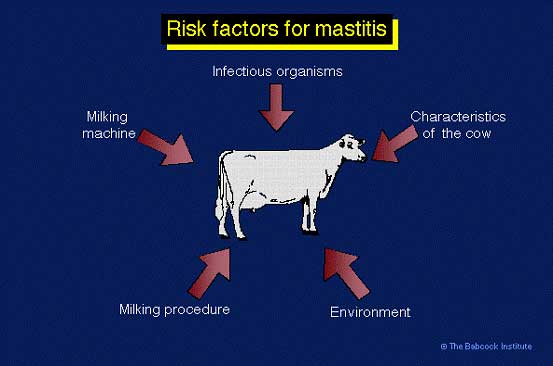

Mastitis Risk Factors - Five Point Plan

The main risk factors for mastitis are shown below:

The Five Point Plan

The five point plan was established by the Milk Marketing Board in the 1950’s in order to counteract the mastitis risk factors – the points are still valid today:

- Hygiene: i.e. improving operator hygiene during milking such as the wearing of gloves and using disposable teat wipes.

- The correct maintenance of milking machine equipment.

- Post-milking teat disinfection.

- The prompt identification of clinical cases, veterinary treatment and the culling of chronic recurrent cases.

- Dry Cow Therapy.

Contagious Mastitis

The main contagious organisms are listed below:

- Staphylococcus aureus

- ‘Cow-adapted’ Streptococcus uberis

- Coagulase negative staph (CNS)

Other organisms which are quite rare but cause serious outbreaks of contagious mastitis are:

- Streptococcus agalactia

- Mycoplasma

- Control of contagious mastitis

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus)

This bacterium is extremely difficult to control by treatment alone, because the response to antibiotic treatment is poor. Successful control is achieved by prevention of new infections and culling infected cows. S. aureus organisms colonize damaged teat ends or teat lesions. The infection is spread form cow to cow by a number of factors e.g. milkers’ hands, wash cloths, teat cup liners, and flies. The organisms probably penetrate the teat canal during milking. Irregular vacuum fluctuations impact milk droplets and bacteria against the teat end with sufficient force to cause teat canal penetration and possible development of new infection. Infected cows must either be culled, segregated from the milking herd and milked last or milked with separate milking units, or teat cup liners must be rinsed and sanitized after milking infected cows. The development of automatic dipping and flushing through the cluster has the potential to revolutionise the control of S. aureus mastitis.

Staphylococcus aureus causes chronic mastitis, often it is subclinical, where there is neither abnormal milk nor detectable change in the udder, but somatic cell count has increased. Some cows may flare-up with clinical mastitis, especially after calving. The bacteria persist in mammary glands, teat canals, and teat lesions of infected cows and are considered contagious. The infection is spread at milking time, when S. aureus contaminated milk from infected cows comes into contact with teats of uninfected cows, and the bacteria penetrate the teat canal. Once established, S. aureus often does not respond to antibiotic treatment, and infected cows eventually must be segregated or culled from the herd. Eradication of S. aureus, has proved to be almost impossible; however control is possible by practicing the highest level of hygiene and milking techniques.

Cows infected with S.aureus do not necessarily have high SCCs. Only 60% of infections are found in cows producing milk with more than 200,000 SCC. In several research trials, 3-8% of first lactation cows were found infected with S. aureus at calving. Many remain infected throughout the first lactation and are reservoirs for infecting other cows in the herd. Although as many as half of the cows with high SCC may be infected with S. aureus, somatic cell counts alone are not sensitive enough to positively diagnose S. aureus infections.

Streptococcus agalactiae

This infection is now quite rare; it is caused by poor hygiene and milking plant maintenance. Take care not to buy it in with replacements!

Since 2000 there has been a small rise in incidence due to corner cutting as a result of poor milk prices.

The infection causes massive bacterial counts 10 million or more in a cow!

The organism inhabits ducts and cisterns in the mammary gland, however it does not survive in environment and can be eliminated by simultaneous herd treatment.

The infection causes inflammation which blocks ducts and leads to decreased milk production and increased somatic cell counts.

Control of Contagious Mastitis

Quarantine Infected Cows

Keep infected cows in a separate treatment group and milk them last or use a separate claw and bucket.

Teat Dipping - Germicidal Dips

Postmilking teat dipping with germicidal dips is recommended. Barrier dips are useful against environmental infection but their effect against the contagious pathogens appears to be lower than that of germicidal dips.

Dry Cow Therapy

Treat all quarters with dry cow antibiotics at end of lactation, this is essential.

Special Treatments at Drying off

Some cows with a history of mastitis or raised cell counts require special additional treatment t drying off.

ADF (auto dip/fush) - (backflushing)

The cost of these units is coming down all the time; probably the best way of stopping transfer of infection.

Flush milk claws (hot water or germicide) after milking infected cows

If using a germicide ensure that it is licenced for this purpose.

Use individual cloth/paper towels to wash/dry teats

Hygiene

Clean hands (wear gloves). good hygiene and teat preparation.

Milking Machine Maintainence

Malfunctioning milking machines that result in frequent liner slips and teat impacts can increase cases of environmental mastitis. Ensure your machine is cheched by a technician regularly and any faults rectified as soon as possible. Also make sure your liners are replaced at the correct time – a simple calculation is shown below:

Liner life = 2,500 x number of milking units

Number of cows x 2*

* milked twice daily.

A poorly maintained milking plant will cause teat end lesions which allow infections to enter the teat canal.

Avoid buying infected cows

Always check cell count history of individual cows and the herd of origin as a minimum requirement.

Cull persistently infected cows

Environmental Mastitis

The main causes of environmental mastitis are:

- Escherichia coli (E.Coli)

- Streptococcus uberis

- Pseudomonas species

Streptococcus uberis (Strept uberis)

Strepuberis mastitis is probably the most important organism with regard to mastitis in the modern dairy cow. It is an environmental organism (Control of environmental mastitis) that lives in faeces, the rumen and in all areas where there is cow contact. Whilst it is an easy organism to kill in a petri dish it is very difficult to eradicate from an infected udder. The organism may progress from being an environmental cause of infection to a contagious cause by becoming cow-adapted (Control of contagious mastitis). In other words the organism lives in the udder and transmits to other cows during the milking process in the same way as S.aureus. Large clinical outbreaks of strep uberis can result in high and fluctuating bactoscans as well as raised herd SCC.

Treatment of Strep uberis mastitis must be aggressive and targeted with specific treatment protocols. If treatment is not aggressive then there is more likelihood of cow-adapted infections developing. This is why many farms fail in their attempts to control and treat strep uberis mastitis.

Pseudomonas

The clinical signs are similar to E. coli. Pseudomonas mastitis is usually a result of a hygiene problem in the parlour. It generally causes infection from contaminated water, pipes, heater, wash hoses, teat dip. It is often resistant to many antibiotics

Control of Environmental Mastitis

1. Housing and Environment

Housed cows are at greater risk for environmental mastitis than cows on pasture. However in the summer oubreaks of environmental mastitis often occur, these are due to either high rainfall or very hot weather which causes the cows to shelter under trees and produce a very contaminated area. Sources of environmental pathogens include manure, bedding, feedstuffs, dust, dirt, mud, and water.

Bedding materials are a significant source of teat end exposure to environmental pathogens. The number of bacteria in bedding fluctuates depending on contamination (and, therefore, availability of nutrients), available moisture, and temperature. Low-moisture inorganic materials, such as sand or crushed limestone, are preferable to finely chopped organic materials. In general, drier bedding materials are associated with lower numbers of pathogens. Warmer environmental temperatures favor growth of pathogens; lower temperatures tend to reduce growth.

Finely chopped organic bedding materials, such as sawdust, shavings, recycled manure, pelleted corncobs, peanut hulls, and chopped straw, frequently contain very high coliform and streptococcal numbers. With clean, long straw, coliform numbers are generally low; but the environmental streptococcal numbers may be high.

Attempts to maintain low coliform numbers by applying chemical disinfectants or lime are generally impractical because frequent, if not daily, application is required to achieve results. Total daily replacement of organic bedding in the back third of stalls has been shown to reduce exposure of teat ends to coliform bacteria.

Environmental conditions that can increase exposure include: overcrowding; poor ventilation; inadequate manure removal from the back of stalls, alleyways, feeding areas and exercise lots; poorly maintained (hollowed out) free stalls; access to farm ponds or muddy exercise lots; dirty maternity stalls or calving areas; and general lack of farm cleanliness and sanitation.

Control of environmental mastitis is achieved by decreasing teat end exposure to potential pathogens or by increasing the cow’s resistance to mastitis pathogens.

2. Teat Dipping - Germicidal Dips

Premilking dipping is advocated for the control of environmental pathogens and is certainly recommended in herds where there is a high risk of either E.coli or Strep uberius infections.

Postmilking teat dipping with germicidal dips is recommended. A degree of control over the environmental streptococci is exerted, but there is no control of coliform intramammary infection.

3. Teat Dipping - Barrier Dips

Barrier dips, postmilking, are reported to reduce new coliform intramammary infections. Their efficacy against the environmental streptococci and the contagious pathogens appears to be lower than that of germicidal dips.

4. Dry cow therapy and teat sealants

Dry cow therapy with the use of teat sealants of all quarters of all cows is recommended. Dry cow antibiotic therapy significantly reduces any infections carried over from the previous lactation and the teat sealant prevents new environmental infections.

5. Backflushing or use of germicidal sprays between cows

Ensure the product you are using is licenced to be used in this way. This proceedure is usefull in preventing the spread of cow-adapted strep uberis infection, However it does not prevent initial environmental mastitis infection.

6. Milking machine problems

Malfunctioning milking machines that result in frequent liner slips and teat impacts can increase cases of environmental mastitis. Ensure your machine is cheched by a technician regularly and any faults rectified as soon as possible. Also make sure your liners are replaced at the correct time – a simple calculation is shown below:

Liner life = 2,500 x number of milking units

Number of cows x 2*

* milked twice daily.

A poorly maintained milking plant will cause teat end lesions which allow infections to enter the teat canal.

7. Udder preparation

Milking cows with wet udders and teats is likely to increase the incidence of environmental mastitis. Teats should be clean and dry prior to attaching the milking unit. Washing the teats, not the udder, is recommended.

8. Vaccination

There is a vaccine available for mmunizing cows during the dry period against Escherichia coli J-5 bacterin. This vaccine will reduce the number and severity of E.coli clinical mastitis cases during early lactation.

9. Diet

Feeding diets deficient in vitamins A or E, beta-carotene, or the trace minerals selenium, copper, and zinc will result in an increased incidence of environmental mastitis. The supplementation of the dry cow diet with Selenium has been shown to be of benefit.